On Small Seasons and Long Calendars

Recently, I felt an odd longing for seasons.

San Francisco has only two: pleasant and foggy. Trees keep their leaves year-round, and temperatures are consistently in the sweater range. It’s a city of eternal mild weather.

This past December I went back to Toronto when winter was in full force. My phone told me it was -30°C. The downtown core was like a wind tunnel, blasting my face with high-speed frigid air. Why does anyone put up with this? I thought. But here I am, five months later, sitting in the California sun, longing for some crappier weather.

It’s not the Canadian winters that I miss so much as the way seasons naturally divide the year.

Living in a season-less city makes time move at a scary pace, like how as a kid, summer vacation would end before you know it. Between work, travel, and a few personal projects, weeks pass by in an instant. I’ve been here for two years, but it’s only felt like a couple months.

A farmer consulting the local almanac. From the US Library of Congress.

Few tools have been as important to humanity as calendars. Shortly after writing systems developed, calendars were found. It makes sense: in agricultural days it was important to know when in the year to plough, to seed, to harvest and when to let fields lie fallow.

Every culture developed their own local calendars to track the time, often sharing the definition of day (an easy one), but varying from one region to the next in concepts like weeks, months, and years.

As societies urbanized, these measurements were standardized. Over time weeks and months were defined and consolidated into either a moon-phase-based lunisolar calendar, or a sun-path based solar calendar (the latter being the origin for the Gregorian calendar we use today). Standardizing weeks and months was important: by having a shared language for time, you can now talk with the town over about if winter is coming early this year, or when the next holy day is, or even just speak meaningfully about the future.

There’s no shortage of writing on our mechanization of time, but McLuhan is particularly concise:

The clock [or calendar, in our case] dragged man out of the world of seasonal rhythms and recurrence, as effectively as the alphabet had released him from the magical resonance of the spoken word and the tribal trap.

Like written language, the development of a standard calendar enabled stronger coordination and control for countries and societies. And also like written language, standard calendars introduced shared metaphors and patterns of thought. The week, the month, the year, sure. But also the financial quarter, the nine-to-five, the holiday.

This language shapes how we think about time and hence how we think about our lives and work.

For instance, my roommates work at larger companies, and have projects which are constrained to the current financial quarter. They often come home frustrated, feeling like they can’t make meaningful progress because of the short cadence. It encourages decisions that quickly cater to metrics, rather than working towards about more meaningful, holistic changes. The chunks of time are too small, too constraining.

The inverse happens every New Year’s Eve. People set resolutions that are achievable within a year, but as the days pass, lose themselves in how quickly they go by. The cadence for reflection and review is often too long, and the goals become disconnected from everyday experience, nebulous and intangible.

Both of these experiences point to, in part, a failure of how we conceptualize and represent time. Using years and quarters to divide time often feels quite … arbitrary.

Standardized calendars are no doubt great for accounting, communication, and coordination1 but they fail at more personal functions like doing deep work, or maintaining cycles of interest and curiosity.

”Phases”

A friend of mine has a unique method of journaling.

He documents moments from his life via a mishmash of words, events, ideas, and screenshots, and groups them into discrete phases in iPhoto. Each phase is roughly two weeks long — but it’s defined by his living situation and activities, not the days of the month. A week-long bike trip across Southern Europe might be one phase, but two months of heads-down focus on school work could be another.

It’s a great way to remember things. In conversations, a topic or feeling will come up, only for him to say, “oh man, that was so phase 37.” By chunking his life out into phases it becomes easier to grasp, both in language and in memory.

Contrast that with a more standard journaling experience: writing a couple hundred words every few days. At the end of a month or a year, you look back on a sea of sentences, unfiltered and uncategorized. So much is written that it’s hard to extract anything meaningful from it without jumping around to specific days.

By eschewing a standard period for a self-defined one, my friend has inadvertently created a personal unit of time.

Thinking in Decades

Consider another function of calendars: planning.

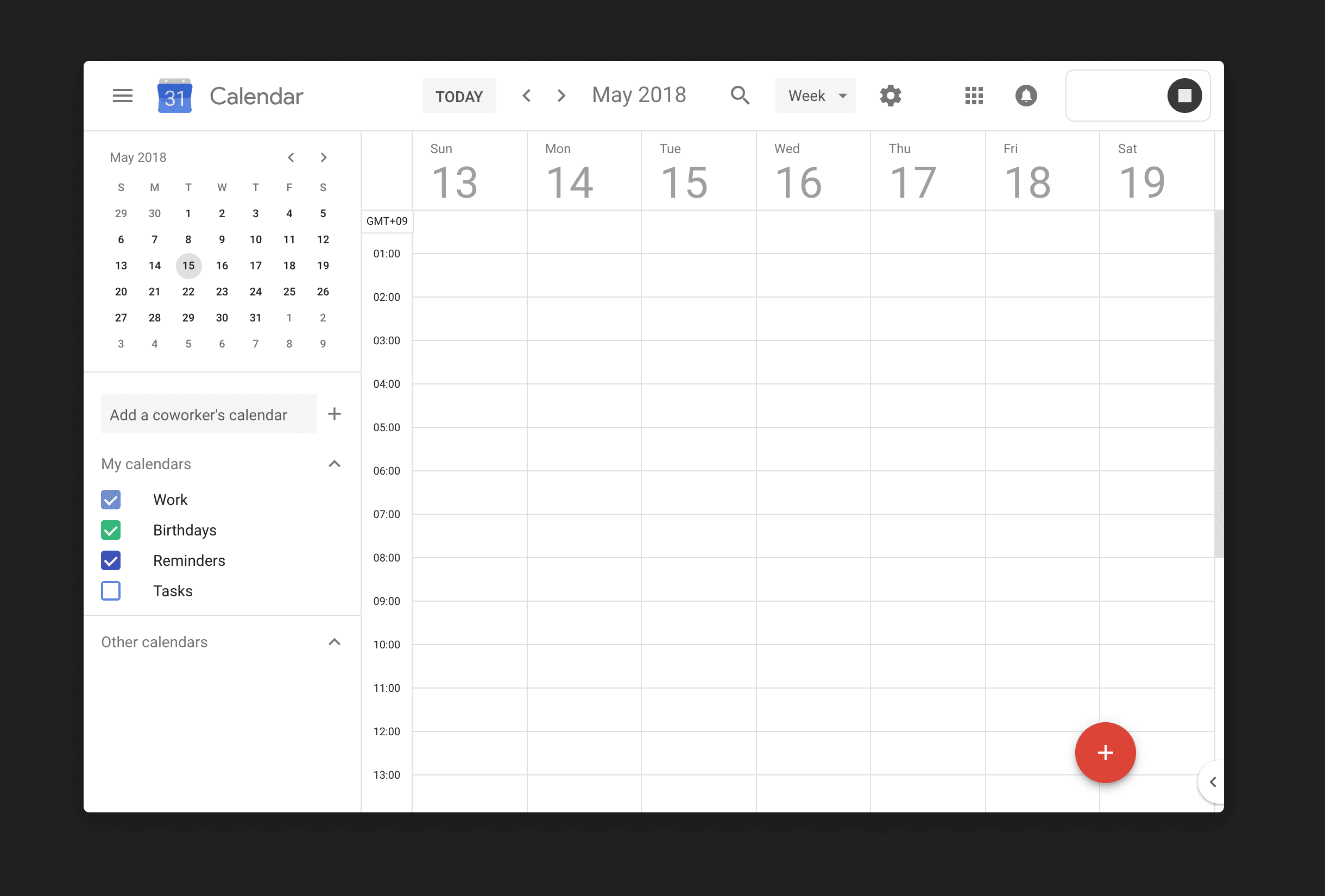

You open up Google Calendar and you get a view of the next 7 days. You can block out the next 168 hours of your life in 30 minute events.

But unless your life is a long series of back-to-back 30 minute meetings, does this interface make sense? Do most people actually live that way?

In contrast, James Fisher’s long calendar idea sounds really compelling:

How long will you be in your current house? How do you plan out your thirties? When will you move to Spain, as you’ve always imagined you would? When might you have your first child, and what job would you like to aim for by then? […]

These life questions require a different kind of calendar. They operate on a different timescale, where the month is probably the most granular unit of time you might want. These questions work on a personal human epoch — “I am 29”, not “it is 2017.”

How might seeing your whole life, laid out on a single surface affect how you live and plan?

Small Seasons

In Kenya Hara’s book White, he briefly talks about sekki, small seasons used in ancient agricultural China and Japan to divide the year. Each sekki corresponds to a shift in the climate, not the calendar, with poetic language to match the changes.

Where spring is our “large” season, lasting roughly from March to June, the sekki calendar breaks it down into six small seasons: start of spring, rain waters, the going-out of the worms, vernal equinox, clear and bright, and rain for harvests.2 Both describe a similar period of time, but one does so with a precision that feels much more human.

These days, I increasingly find myself using sekki as a calendar.

On one hand, it’s nice to have a calendar so explicitly based on the surrounding environment; you’re encouraged to look up and notice what’s different today, that the crickets are no longer chirping and that time has gone by.

But it also better matches my own ebb and flow of interest, attention, and general mental headspace. Two weeks of deep focus on something is a healthy amount before I want to move on to a different aspect, or a new project all together.

Sekki, phases, and the long calendar are just a few examples of more human and purposeful calendaring systems. Heck, even a seasonal vegetable chart for an area is an unexpectedly useful time-keeping tool. Why shouldn’t your calendar help you decide when to make a minestrone soup, oxtail stew, or a pico de gallo?

You can imagine some bigger questions along the same train of thought:

- How can calendars inspire or inform daily living?

- What does a communal calendar look like? How can it afford community action and a sense of collective identity?

- How can calendars encourage thinking beyond our own lifespans? (Peter Bïlak’s 100-year calendar is an interesting example of this)

I’m interested in more conversation and links about this.3 It seems like there’s merit to finding more personal ways of chunking out time. Especially in an era with such powerful means to represent time, finding novel and more meaningful timescales seems like fertile ground for exploration.

But, if nothing else, I’m happier just to notice the time passing a little more often.

Further reading

- Small Seasons

- In Search of Personalized Time

- A Line Moving Across A Window Once Every Year

- Austin Kleon’s notes on seasons, including Seasonal Time

Footnotes

-

Having recently experienced the joys of programming around the Ethiopian calendar, I’m enthusiastically in support of alignment to conventions when working with others. ↩

-

You can find a full list of small seasons here, a small site built to enshrine this idea. ↩

-

If you are too, drop some hot links in this Alternate Calendars Are.na channel. I’d love to see more. ↩